Man and/or woman Pierre Molinier and Catherine Opie

In 2020 I was finishing my education with an internship in the Groninger Museum, where I was able to explore their extensive photography collection when they developed the exhibition ‘What will the neighbors say? Photography from the collection’. I was struck by the amount of queerness I found in that collection that seemed to go unnoticed by the staff. The overlapping themes of unconventionality and controversy were easily recognized, but I don’t think I heard many people say the word ‘gay’ when discussing the exhibition. While selecting and installing the works I was captivated by the fetishism of Pierre Molinier and enamored by the portraits of Catherine Opie, and when I was asked to write an article for the museum’s magazine about the exhibition I set out to highlight the queerness of it all. The article was originally published in Dutch in the first edition of the 2020 Groninger Museum Magazine, which can be found here.

When André Breton, founder of the surrealist movement, wrote his first manifesto in 1924, there wasn’t much left of France. World War I had left so much damage and chaos that the people of France wondered what it had all been for. They started to desperately cling to the values they upheld before the war. Order had to be restored, and fast. Breton watched this happen and found the power of imagination was lost in this development. He was a firm believer in liberating the subconscious and in his manifesto he called for the disruption of rationality and the established order. The art that sprung from this movement was completely incomprehensible for the viewer, and the surrealists were met with their fair share of criticism. The fifties were a far more successful time for the surrealists in terms of reception, however their succes also meant their downfall. As their popularity rose, so did their prices, and the elites they once considered their enemy became their biggest patron. Meanwhile, the country had survived another war. Their hard work to restore order had all been for nothing. The deepest trenches of human subconsciousness and fever dreams could no longer shock or confuse the survivors of the terrible nightmare that was real life. In this drag, where order and chaos were more and more difficult to tell apart, André Breton discovered Pierre Molinier.

The French Molinier was glorified by Breton as a genius, as the ‘wizard of erotic art’. Nowadays Molinier is often dubbed the ‘forgotten surrealist’. He would usually pose in his own photographs, dressed in corsets, stockings and stiletto heels, after which he’d drastically manipulate his appearance through photomontage. In Travesti (1969), Molinier stuck a photo of himself at age 17 onto his current body, possibly in an attempt to retrieve his youthful beauty. The ever-changing process of photomontage reflects his own sexuality and identity. To Molinier the technique was the perfect way to transform himself into the ideal androgynous human.

Pierre Molinier, Travesti, 1969

Originally Molinier was a painter of symbolist and post-impressionist tradition, and he mostly took photos for his own pleasure. Not just for the end result, the process itself, the transformation and posing, played a huge role in the stimulation Molinier was looking for. In his studio, which he called his ‘boudoir’, he photographed himself in front of the mirror using a self-timer. Living out his fantasies was useless if he could not watch himself doing it. Even in his final moments, after he had become impotent and therefore lost his sexuality, he wanted to watch himself die. In front of the mirror, in his boudoir, he shot himself in the head. 25 years earlier he had constructed his own tombstone and written the obituary: ‘here lies Pierre Molinier, a man without morals’.

Evidently, a man who photographed himself in women’s lingerie and high heels behind closed doors would have been shocking to the public today, let alone in the fifties and sixties. All the better to Molinier and Breton, who sought to shake up surrealism and considered Molinier the man capable of doing so. Unfortunately, in 1965, even Molinier found himself crossing a line. In Oh! Marie… Mere de Dieu (1965) Molinier poses as a hermaphrodite version of Christ. This caused Breton, notoriously homophobic, to ban him from the movement. Molinier, the narcissistic, perverted transvestite who lived the fantasies that other surrealists could only speculate on in their paintings, went down in history as the artist that was too shocking for the surrealist movement.

Pierre Molinier, Oh! Marie… Mere de Dieu, 1965

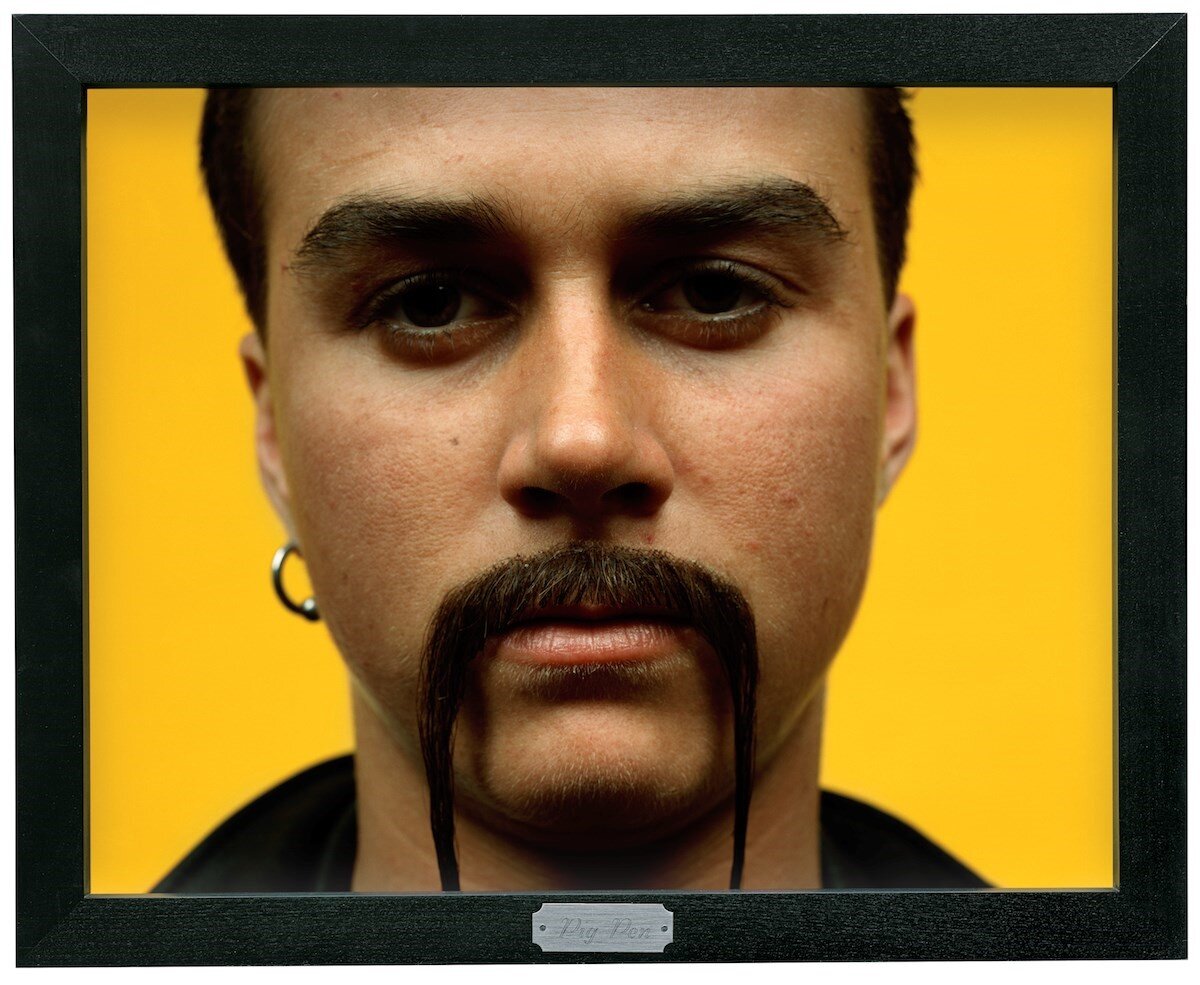

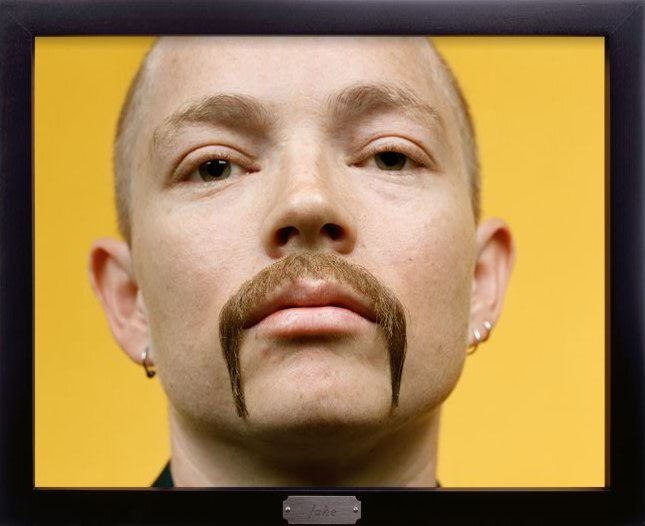

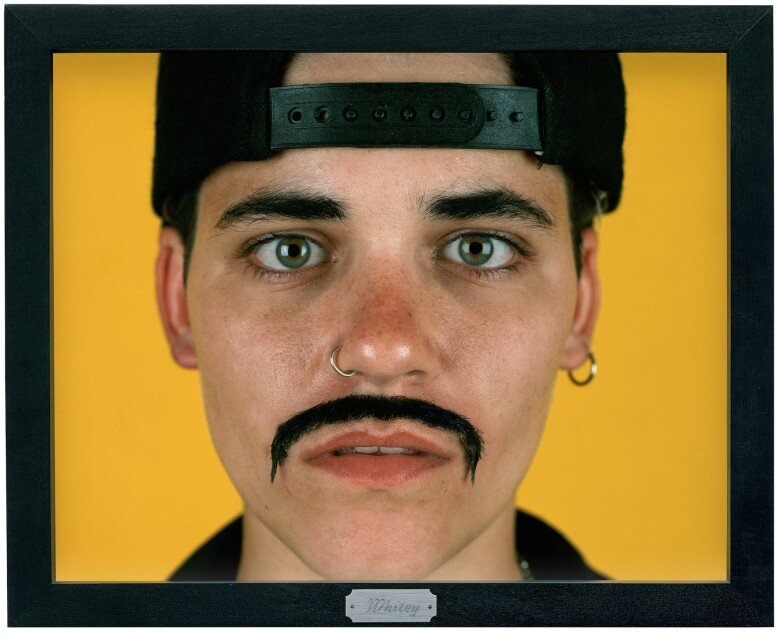

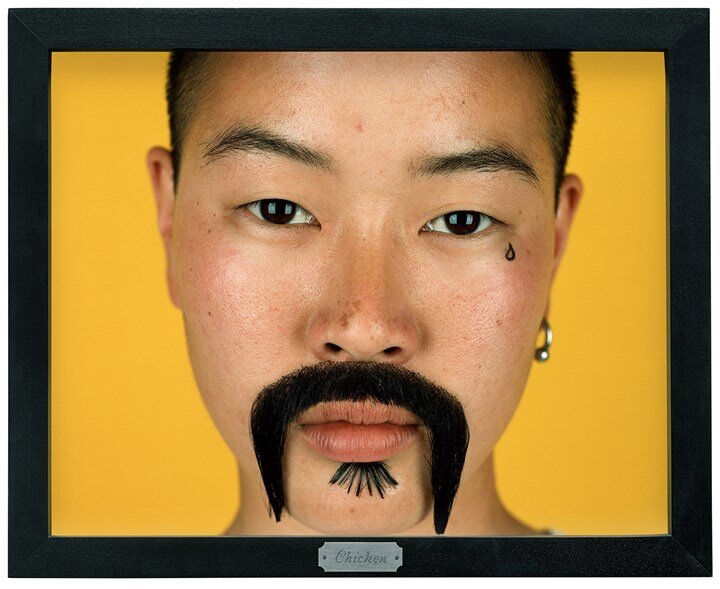

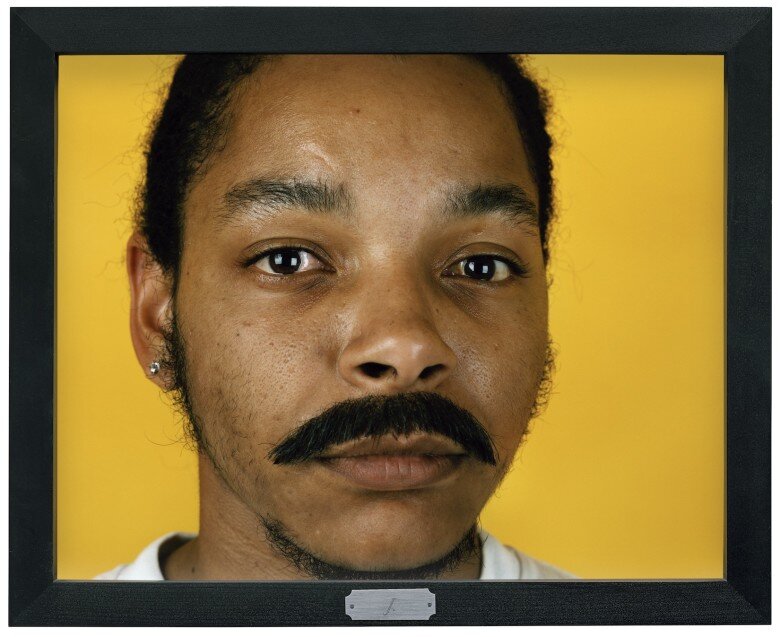

Around the time Molinier was taking his self-portraits, Catherine Opie was born in the American city of Sandusky. Although it’s unknown if Catherine Opie ever saw Molinier’s photographs during that time, she did grow up during the rise of feminism and gender studies. As a young art student in the eighties, Opie started exploring the gay scene in San Fransisco with her camera. This brought forth her first solo exhibition in 1991, Being and Having. Here she photographed herself and her lesbian friends as hypermasculine alter ego’s, sporting fake beards and moustaches. Around the same time, Judith Butler published her book Gender Trouble, where she addresses the performativity of gender and its manifestations. Butler claims that gender is not something we are, but a behaviour. From birth we are fed ideas on what a man or woman is supposed to be, and we adapt. Opie’s portraits are a perfect example of the malleability of gender. The models take control over their appearance and how they are perceived. The conscious decision to wear facial hair destabilizes their status as women, but doesn’t automatically make them men. Their names are engraved in the wooden frames, but except for serving as an identifier they are merely nicknames such as Chicken, Con or Papa Bear, and still don’t give us any indicators on what their genders might be. The portraits demonstrate how easy it is to undermine traditional ideas about gender.

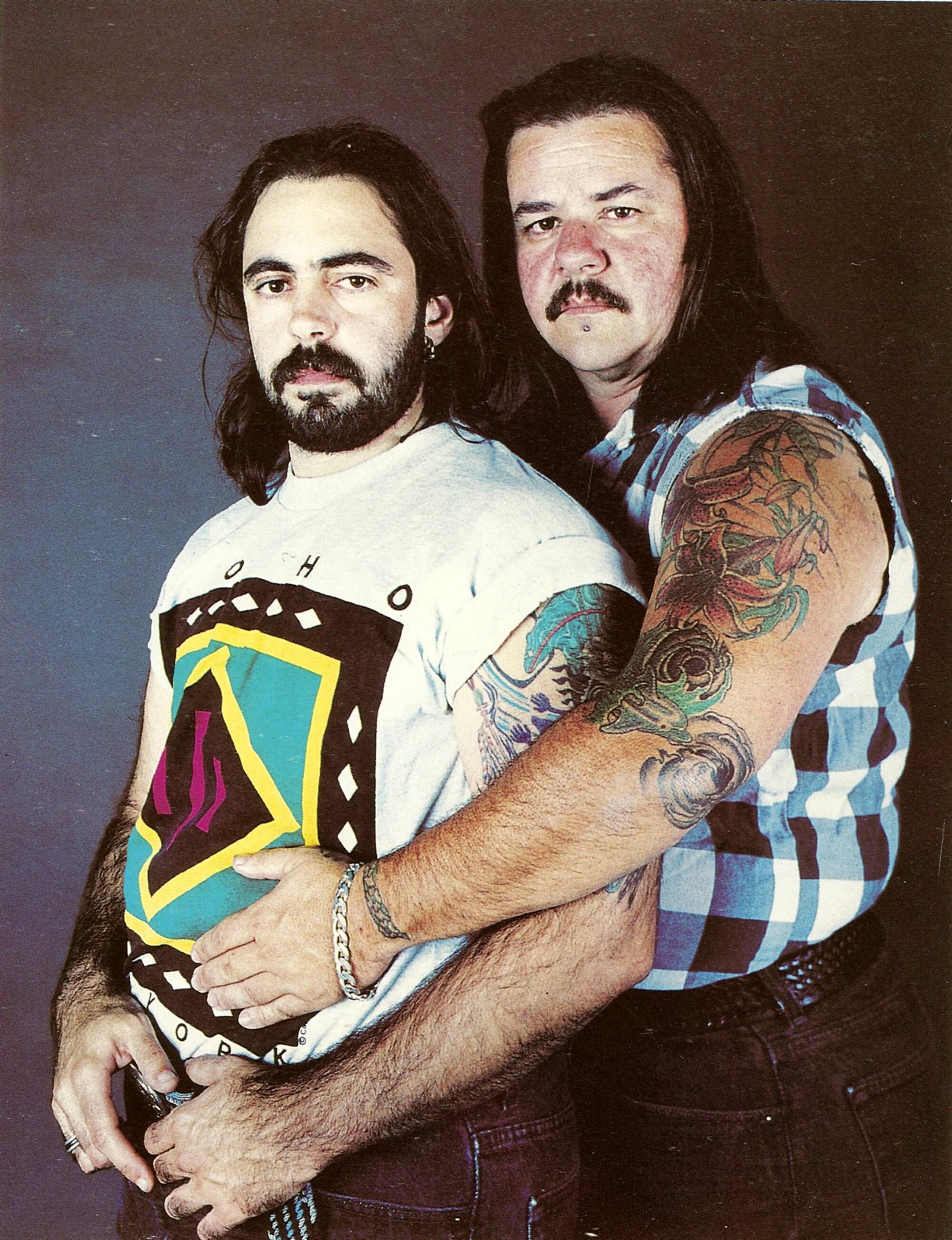

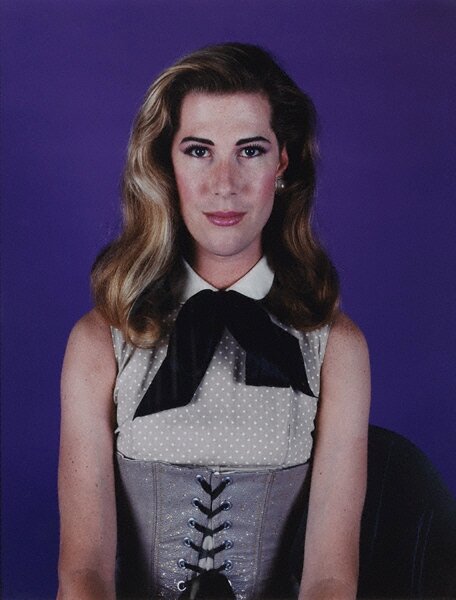

After Being and Having Opie continues portraying her friends in the gay scene of Los Angeles and San Fransisco in the series Portraits. The individuals in these portraits consider the body to be a ‘billboard of identity’, a habit taken from the punk movement. One of the portraits shows Justin Bond, whose name, as opposed to the portraits in Being and Having, does give a clear indication that we would be looking at a man. However, Justin is portrayed with long hair, red lips, fake lashes and a corset over a polka-dot dress. He is dressed as his drag persona Kiki Durane. Justin/Kiki doesn’t believe in unambiguous gender, and invites the viewer to get to know the person in the photograph, regardless of gender. The couple Mike and Sky seem much easier to recognize as men. Yet, they have altered their bodies and appearance through hormones and surgeries in order to appear male, but they still identify as lesbian women. This allowed them to assemble their own identity and the perception thereof, exactly as they want it. The performativity Judith Butler refers to extends a lot further than simply wearing a costume or sticking a fake moustache on your face. Mike and Sky have permanently changed their bodies. Both series of portraits ask us implicitly to ponder the genders of the models and lead us to question our own ideas about gender. The classical compositions and brightly colored backgrounds are reminiscent of old masters such as Hans Holbein. Referring to this type of ‘high art’ in her portraits about gender allows Opie to lure those who might not want to see such images or question such topics. They are confronted with these questions through the vulnerability of the models.

The photographs of Opie and Molinier may not be as shocking as they once were, but no one can deny that they are confronting. Molinier gives us the sense that we are viewing something we aren’t supposed to see, like we are peeping into his private quarters. This discomfort is exactly what he is looking for. Opie’s portraits aren’t nearly as explicit, but the people she portrays don’t have to do much more than exist in order to be considered offensive or unappealing. Their ungendered appearance and the autonomy they demand over their bodies and existence causes confusion to many a viewer, even without the fetishistic theatre that Molinier concerns himself with. We view Opie’s friends with eyes full of questions. Are they a man or a woman? Gay or straight? Is this a costume or not? And they return our question by asking if it matters.